Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that intelligence changes as children grow.

A child’s cognitive development is not just about acquiring knowledge, the child has to develop or construct a mental model of the world.

Cognitive development occurs through the interaction of innate capacities (nature) and environmental events (nurture), and children pass through a series of stages.

About Author

Jean Piaget, (born August 9, 1896, Neuchâtel, Switzerland—died September 16, 1980, Geneva), Swiss psychologist who was the first to make a systematic study of the acquisition of understanding in children. He is thought by many to have been the major figure in 20th-century developmental psychology.

Piaget’s early interests were in zoology; as a youth he published an article on his observations of an albino sparrow, and by 15 his several publications on mollusks had gained him a reputation among European zoologists.

At the University of Neuchâtel, he studied zoology and philosophy, receiving his doctorate in the former in 1918. Soon afterward, however, he became interested in psychology, combining his biological training with his interest in epistemology.

He first went to Zürich, where he studied under Carl Jung and Eugen Bleuler, and he then began two years of study at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1919.

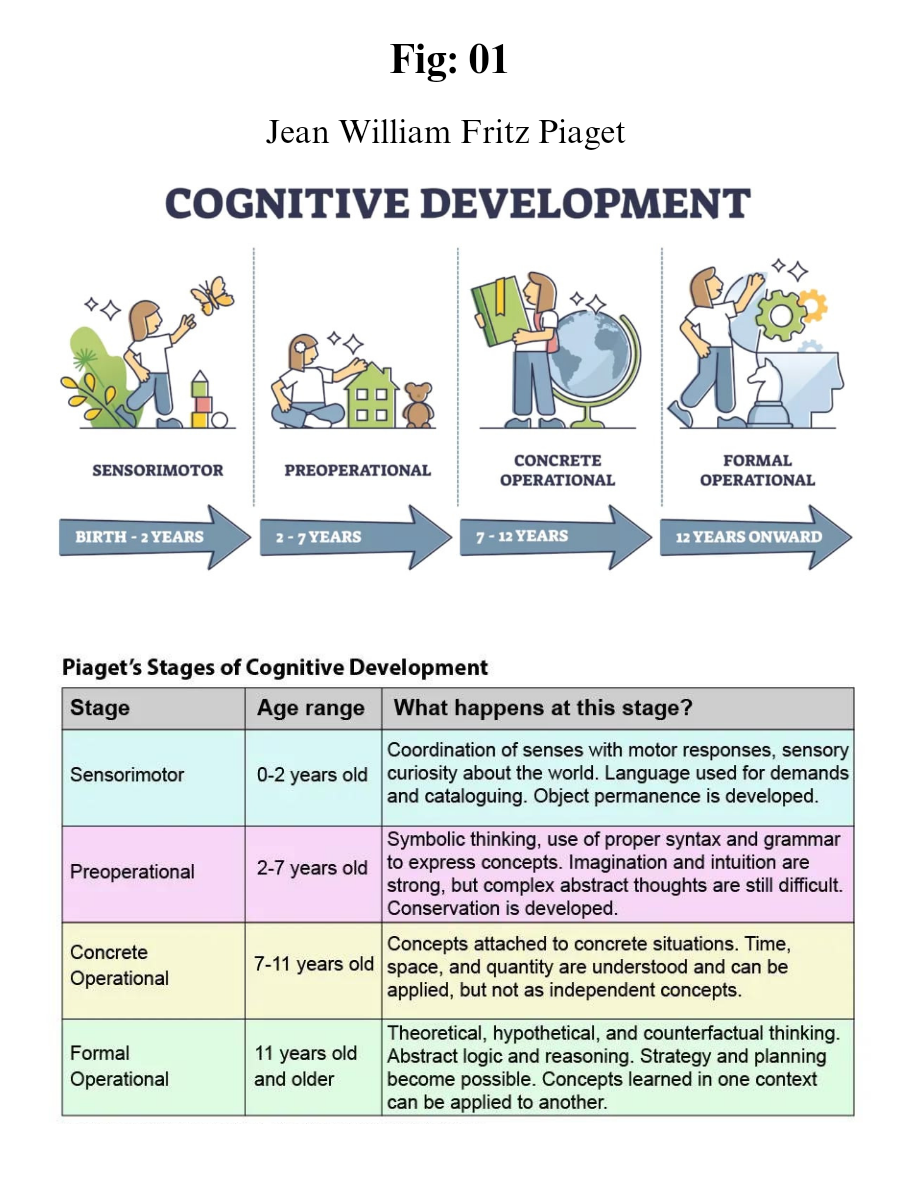

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development proposes 4 stages of development.

1. Sensorimotor stage: birth to 2 years

2. Preoperational stage: 2 to 7 years

3. Concrete operational stage: 7 to 11 years

4. Formal operational stage: ages 12 and up

The sequence of the stages is universal across cultures and follows the same invariant (unchanging) order.

All children go through the same stages in the same order (but not all at the same rate).

Theory Development

Piaget was employed at the Binet Institute in the 1920s, where his job was to develop French versions of questions on English intelligence tests. He became intrigued with the reasons children gave for their wrong answers to the questions that required logical thinking.

He believed that these incorrect answers revealed important differences between the thinking of adults and children.

Piaget branched out on his own with a new set of assumptions about children’s intelligence:

Children’s intelligence differs from an adult’s in quality rather than in quantity. This means that children reason (think) differently from adults and see the world in different ways.

Children actively build up their knowledge about the world. They are not passive creatures waiting for someone to fill their heads with knowledge.

The best way to understand children’s reasoning is to see things from their point of view.

Piaget did not want to measure how well children could count, spell or solve problems as a way of grading their I.Q.

What he was more interested in was the way in which fundamental concepts like the very idea of number, time, quantity, causality, justice, and so on emerged.

Piaget studied children from infancy to adolescence using naturalistic observation of his own three babies and sometimes controlled observation too. From these, he wrote diary descriptions charting their development.

He also used clinical interviews and observations of older children who were able to understand questions and hold conversations.

Stages of Development

Each child goes through the stages in the same order, and child development is determined by biological maturation and interaction with the environment.

At each stage of development, the child’s thinking is qualitatively different from the other stages, that is, each stage involves a different type of intelligence.

Although no stage can be missed out, there are individual differences in the rate at which children progress through stages, and some individuals may never attain the later stages.

Piaget did not claim that a particular stage was reached at a certain age – although descriptions of the stages often include an indication of the age at which the average child would reach each stage.

The Sensorimotor Stage (Ages: Birth to 2 Years)

The first stage is the sensorimotor stage, and during this stage, the infant focuses on physical sensations and on learning to coordinate their body.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

The infant learns about the world through their senses and through their actions (moving around and exploring their environment).

During the sensorimotor stage, a range of cognitive abilities develop. These include: object permanence; self-recognition (the child realizes that other people are separate from them); deferred imitation; and representational play.

They relate to the emergence of the general symbolic function, which is the capacity to represent the world mentally

At about 8 months, the infant will understand the permanence of objects and that they will still exist even if they can’t see them and the infant will search for them when they disappear.

During the beginning of this stage, the infant lives in the present. It does not yet have a mental picture of the world stored in its memory therefore it does not have a sense of object permanence.

If it cannot see something, then it does not exist. This is why you can hide a toy from an infant, while it watches, but it will not search for the object once it has gone out of sight.

The main achievement during this stage is object permanence – knowing that an object still exists, even if it is hidden. It requires the ability to form a mental representation (i.e., a schema) of the object.

Towards the end of this stage the general symbolic function begins to appear where children show in their play that they can use one object to stand for another. Language starts to appear because they realize that words can be used to represent objects and feelings.

The child begins to be able to store information that it knows about the world, recall it and label it.

The Preoperational Stage (Ages: 2 – 7 Years)

Piaget’s second stage of intellectual development is the preoperational stage. It takes place between 2 and 7 years. At the beginning of this stage the child does not use operations, so the thinking is influenced by the way things appear rather than logical reasoning.

A child cannot conserve which means that the child does not understand that quantity remains the same even if the appearance changes.

Furthermore, the child is egocentric; he assumes that other people see the world as he does. This has been shown in the three mountains study.

As the preoperational stage develops egocentrism declines and children begin to enjoy the participation of another child in their games and “lets pretend “ play becomes more important.

Toddlers often pretend to be people they are not (e.g. superheroes, policemen), and may play these roles with props that symbolize real life objects. Children may also invent an imaginary playmate.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

Toddlers and young children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery.

During this stage, young children can think about things symbolically. This is the ability to make one thing, such as a word or an object, stand for something other than itself.

A child’s thinking is dominated by how the world looks, not how the world is. It is not yet capable of logical (problem solving) type of thought.

Moreover, the child has difficulties with class inclusion; he can classify objects but cannot include objects in subsets, which involves classifying objects as belonging to two or more categories simultaneously.

Infants at this stage also demonstrate animism. This is the tendency for the child to think that non-living objects (such as toys) have life and feelings like a person’s.

By 2 years, children have made some progress toward detaching their thoughts from the physical world. However, have not yet developed logical (or “operational”) thought characteristics of later stages.

Thinking is still intuitive (based on subjective judgements about situations) and egocentric (centered on the child’s own view of the world).

The Concrete Operational Stage (Ages: 7 – 11 Years)

By the beginning of the concrete operational stage, the child can use operations (a set of logical rules) so she can conserve quantities, she realizes that people see the world in a different way than he does (decentring) and he has improved in inclusion tasks. Children still have difficulties with abstract thinking.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

During this stage, children begin to think logically about concrete events.

Children begin to understand the concept of conservation; understanding that, although things may change in appearance, certain properties remain the same.

During this stage, children can mentally reverse things (e.g. picture a ball of plasticine returning to its original shape).

During this stage, children also become less egocentric and begin to think about how other people might think and feel.

The stage is called concrete because children can think logically much more successfully if they can manipulate real (concrete) materials or pictures of them.

Piaget considered the concrete stage a major turning point in the child’s cognitive development because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought. This means the child can work things out internally in their head (rather than physically try things out in the real world).

Children can conserve number (age 6), mass (age 7), and weight (age 9). Conservation is the understanding that something stays the same in quantity even though its appearance changes.

But operational thought is only effective here if the child is asked to reason about materials that are physically present. Children at this stage will tend to make mistakes or be overwhelmed when asked to reason about abstract or hypothetical problems.

The Formal Operational Stage (Ages: 12 and Over…)

The formal operational period begins at about age 11. As adolescents enter this stage, they gain the ability to think in an abstract manner, the ability to combine and classify items in a more sophisticated way, and the capacity for higher-order reasoning.

Adolescents can think systematically and reason about what might be as well as what is (not everyone achieves this stage).. This allows them to understand politics, ethics, and science fiction, as well as to engage in scientific reasoning.

Adolescents can deal with abstract ideas: e.g. they can understand division and fractions without having to actually divide things up, and solve hypothetical (imaginary) problems.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

Concrete operations are carried out on things whereas formal operations are carried out on ideas. Formal operational thought is entirely freed from physical and perceptual constraints.

During this stage, adolescents can deal with abstract ideas (e.g. no longer needing to think about slicing up cakes or sharing sweets to understand division and fractions).

They can follow the form of an argument without having to think in terms of specific examples.

Adolescents can deal with hypothetical problems with many possible solutions. E.g. if asked ‘What would happen if money were abolished in one hour’s time? they could speculate about many possible consequences.

From about 12 years children can follow the form of a logical argument without reference to its content. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract concepts, and logically test hypotheses.

This stage sees the emergence of scientific thinking, formulating abstract theories and hypotheses when faced with a problem.

Schemas

Piaget claimed that knowledge cannot simply emerge from sensory experience; some initial structure is necessary to make sense of the world.

According to Piaget, children are born with a very basic mental structure (genetically inherited and evolved) on which all subsequent learning and knowledge are based.

Schemas are the basic building blocks of such cognitive models, and enable us to form a mental representation of the world.

Piaget (1952, p. 7) defined a schema as: “a cohesive, repeatable action sequence possessing component actions that are tightly interconnected and governed by a core meaning.”

In more simple terms, Piaget called the schema the basic building block of intelligent behavior – a way of organizing knowledge. Indeed, it is useful to think of schemas as “units” of knowledge, each relating to one aspect of the world, including objects, actions, and abstract (i.e., theoretical) concepts.

Wadsworth (2004) suggests that schemata (the plural of schema) be thought of as “index cards” filed in the brain, each one telling an individual how to react to incoming stimuli or information.

When Piaget talked about the development of a person’s mental processes, he was referring to increases in the number and complexity of the schemata that a person had learned.

When a child’s existing schemas are capable of explaining what it can perceive around it, it is said to be in a state of equilibrium, i.e., a state of cognitive (i.e., mental) balance.

Operations are more sophisticated mental structures which allow us to combine schemas in a logical (reasonable) way.

As children grow they can carry out more complex operations and begin to imagine hypothetical (imaginary) situations.

Apart from the schemas we are born with schemas and operations are learned through interaction with other people and the environment.

Piaget emphasized the importance of schemas in cognitive development and described how they were developed or acquired.

A schema can be defined as a set of linked mental representations of the world, which we use both to understand and to respond to situations. The assumption is that we store these mental representations and apply them when needed.

Applying Piaget’s Theory to the Classroom

Think of old black and white films that you’ve seen in which children sat in rows at desks, with ink wells, would learn by rote, all chanting in unison in response to questions set by an authoritarian old biddy like Matilda.

Children who were unable to keep up were seen as slacking and would be punished by variations on the theme of corporal punishment. Yes, it really did happen and in some parts of the world still does today.

Piaget is partly responsible for the change that occurred in the 1960s and for your relatively pleasurable and pain free school days.

How to Teach

Within the classroom learning should be student-centered and accomplished through active discovery learning. The role of the teacher is to facilitate learning, rather than direct tuition.

Because Piaget’s theory is based upon biological maturation and stages, the notion of “readiness” is important. Readiness concerns when certain information or concepts should be taught.

According to Piaget’s theory children should not be taught certain concepts until they have reached the appropriate stage of cognitive development.

According to Piaget (1958), assimilation and accommodation require an active learner, not a passive one, because problem-solving skills cannot be taught, they must be discovered.

Therefore, teachers should encourage the following within the classroom:

Educational programs should be designed to correspond to Piaget’s stages of development. Children in the concrete operational stage should be given concrete means to learn new concepts e.g. tokens for counting.

Devising situations that present useful problems, and create disequilibrium in the child.

Focus on the process of learning, rather than the end product of it. Instead of checking if children have the right answer, the teacher should focus on the student’s understanding and the processes they used to get to the answer.

Child-centered approach. Learning must be active (discovery learning).

Children should be encouraged to discover for themselves and to interact with the material instead of being given ready-made knowledge.

Accepting that children develop at different rates so arrange activities for individual children or small groups rather than assume that all the children can cope with a particular activity.

Using active methods that require rediscovering or reconstructing “truths.”

Using collaborative, as well as individual activities (so children can learn from each other).

Role of the Teacher

Evaluate the level of the child’s development so suitable tasks can be set.

Adapt lessons to suit the needs of the individual child (i.e. differentiated teaching).

Be aware of the child’s stage of development (testing).

Teach only when the child is ready. i.e. has the child reached the appropriate stage.

Providing support for the “spontaneous research” of the child.

Using collaborative, as well as individual activities.

Devising situations that present useful problems, and create disequilibrium in the child.

Educational Implications of Piaget’s Theory

The application of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development theory in classroom should be done as follows:

Based on the developmental level of children, the curriculum should provide the required educational experience.

Classroom activities that encourage and assist self learning must be incorporated.

Practical learning situations must be included in the class.

Co-curricular activities that enhance children’s cognitive development must be given equal importance as curricular activities.

The teaching method must be simple to complex and the inclusion of the project teaching method is recommended.

Children learn and think differently from adults therefore, they should be taught accordingly.

The discovery approach to learning must be emphasized.