Hematopoiesis is the production of all of the cellular components of blood and blood plasma. It occurs within the hematopoietic system, which includes organs and tissues such as the bone marrow, liver, and spleen.

Simply, hematopoiesis is the process through which the body manufactures blood cells. It begins early in the development of an embryoTrusted Source, well before birth, and continues for the life of an individual.

It’s easier to remember what hematopoiesis is when you consider its roots. Hematopoiesis is derived from two Greek words:

Haîma: Blood.

Poiēsis: To make something.

Put these words together, and you get hematopoiesis, the process of making blood. Hematopoiesis is also called hemopoiesis, hematogenesis and hemogenesis.

The blood is made up of more than 10 different cell types. Each of these cell types falls into one of three broad categories:

1. Red blood cells (erythrocytes): These transport oxygen and hemoglobin throughout the body.

2. White blood cells (leukocytes): These support the immune system. There are several different types of white blood cells:

a. Lymphocytes: Including T cells and B cells, which help fight some viruses and tumors.

b. Neutrophils: These help fight bacterial and fungal infections.

c. Eosinophils: These play a role in the inflammatory response, and help fight some parasites.

d. Basophils: These release the histamines necessary for the inflammatory response.

e. Macrophages: These engulf and digest debris, including bacteria.

3. Platelets (thrombocytes): These help the blood to clot.

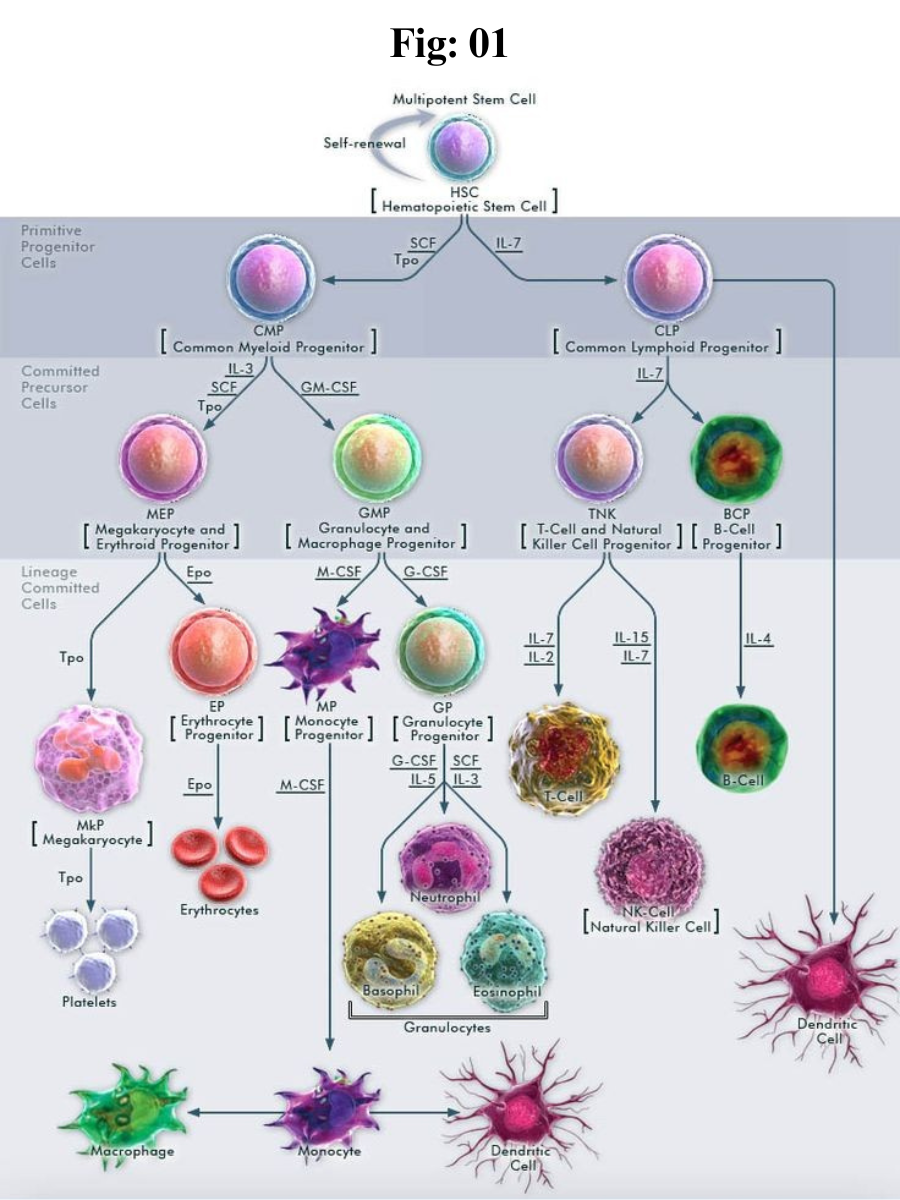

Current research endorses a theory of hematopoiesis called the monophyletic theory. This theory says that one type of stem cell produces all types of blood cells.

Production place:

Hematopoiesis occurs in many places:

Hematopoiesis in the embryo:

Sometimes called primitive hematopoiesis Trusted Source, hematopoiesis in the embryo produces only red blood cells that can provide developing organs with oxygen. At this stage in development, the yolk sac, which nourishes the embryo until the placenta is fully developed, controls hematopoiesis.

As the embryo continues to develop, the hematopoiesis process moves to the liver, the spleen, and bone marrow, and begins producing other types of blood cells.

In adults, hematopoiesis of red blood cells and platelets occurs primarily in the bone marrow. In infants and children, it may also continue in the spleen and liver.

The lymph system, particularly the spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus, produces a type of white blood cell called lymphocytes. Tissue in the liver, spleen, lymph nodes and some other organs produce another type of white blood cells, called monocytes.

The process of hematopoiesis:

The rate of hematopoiesis depends on the body’s needs. The body continually manufactures new blood cells to replace old ones. About 1 percent of the body’s blood cells must be replaced every day.

White blood cells have the shortest life span, sometimes surviving just a few hours to a few days, while red blood cells can last up to 120 days or so.

The process of hematopoiesis begins with an unspecialized stem cell. This stem cell multiplies, and some of these new cells transform into precursor cells. These are cells that are destined to become a particular type of blood cell but are not yet fully developed. However, these immature cells soon divide and mature into blood components, such as red and white blood cells, or platelets.

Although researchers understand the basics of hematopoiesis, there is an on-ongoing scientific debate about how the stem cells that play a role in hematopoiesis are formed.

Hematopoiesis begins with an originator cell common to all blood cell types. It’s called a hematopoietic stem cell (HSC). An HSC develops into a precursor cell, or “blast” cell. A precursor cell is on track to become a specific type of blood cell, but it’s still in the early stages. A precursor cell goes through several cell divisions and changes before it becomes a fully mature blood cell.

The specific types of hematopoiesis include:

Erythropoiesis: Red blood cell production.

Leukopoiesis: White blood cell production.

Thrombopoiesis: Platelet production.

With each change, an originator cell becomes more specialized — less like a stem cell and more like a red blood cell, white blood cell or platelet.

Types:

Each type of blood cell follows a slightly different path of hematopoiesis. All begin as stem cells called multipotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). From there, hematopoiesis follows two distinct pathways.

Trilineage hematopoiesis refers to the production of three types of blood cells: platelets, red blood cells, and white blood cells. Each of these cells begins with the transformation of HSC into cells called common myeloid progenitors (CMP).

After that, the process varies slightly. At each stage of the process, the precursor cells become more organized:

Red blood cells and platelets

Red blood cells: CMP cells change five times before finally becoming red blood cells, also known as erythrocytes.

Platelets: CMP cells transform into three different cell types before becoming platelets.

White blood cells:

There are several types of white blood cells, each following an individual path during hematopoiesis. All white blood cells initially transform from CMP cells into myeoblasts. After that, the process is as follows:

Before becoming a neutrophil, eosinophil, or basophil, a myeloblast goes through four further stages of development.

To become a macrophage, a myeloblast has to transform three more times.

A second pathway of hematopoiesis produces T and B cells.

T cells and B cells

To produce lymphocytes, MHCs transform into cells called common lymphoid progenitors, which then become lymphoblasts. Lymphoblasts differentiate into infection-fighting T cells and B cells. Some B cells differentiate into plasma cells after exposure to infection.

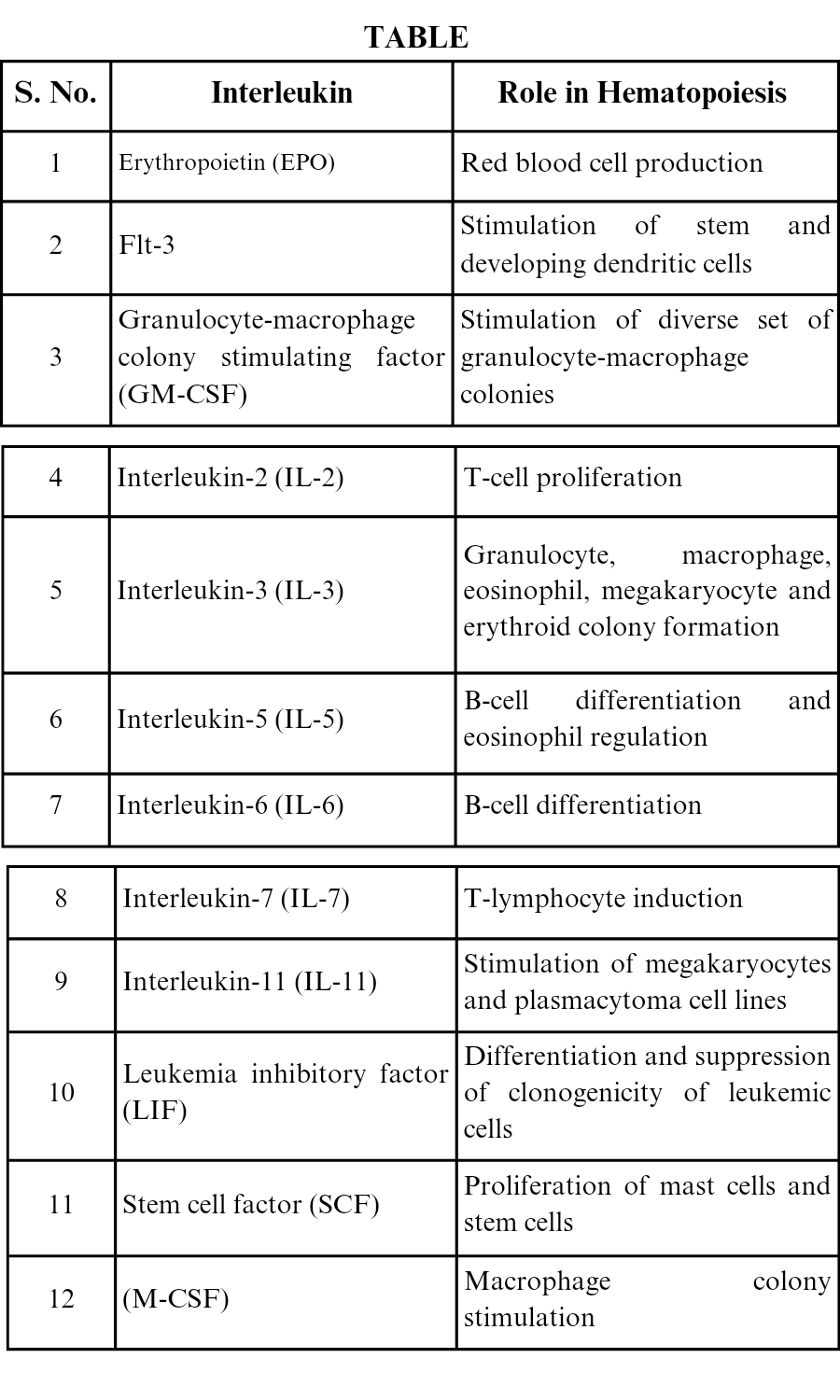

Hematopoietic Cytokines

Hematopoietic cytokines are a large family of extracellular ligands that stimulate hematopoietic cells to differentiate into eight principle types of blood cells. Numerous cytokines are involved in the regulation of hematopoiesis within a complex network of positive and negative regulators. Some cytokines have very narrow lineage specificities of their actions, while many others have rather broad and overlapping specificity ranges.

Listed within this section are the cytokines whose predominant action appears to be the stimulation or regulation of hematopoietic cells. This includes GM-CSF, G-CSF, M-CSF, interleukins, EPO and TPO. There are a number of other cytokines that exert profound effects on the formation and maturation of hematopoietic cells, which include stem cell factor (SCF), flt-3/flk-2 ligand (FL) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). Other cytokines or ligands such as jagged-1, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) also play significant roles in modulating hematopoiesis.

Impact on Health:

Some blood disorders can affect healthy blood cells in the blood, even when hematopoiesis occurs.

For example, cancers of the white blood cells such as leukemia and lymphoma can alter the number of white blood cells in the bloodstream. Tumors in hematopoietic tissue that produces blood cells, such as bone marrow can affect blood cell counts.

The aging process can increase the amount of fat present in the bone marrow. This increase in fat can make it harder for the marrow to produce blood cells. If the body needs additional blood cells due to an illness, the bone marrow is unable to stay ahead of this demand. This can cause anemia, which occurs when the blood lacks hemoglobin from red blood cells.

Conclusion:

Hematopoiesis is a constant process that produces a massive number of cells. Estimates vary, and the precise number of cells depends on individual needs. But in a typical day, the body might produce 200 billion red blood cells, 10 million white blood cells, and 400 billion platelets.

-----*****-----