Introduction

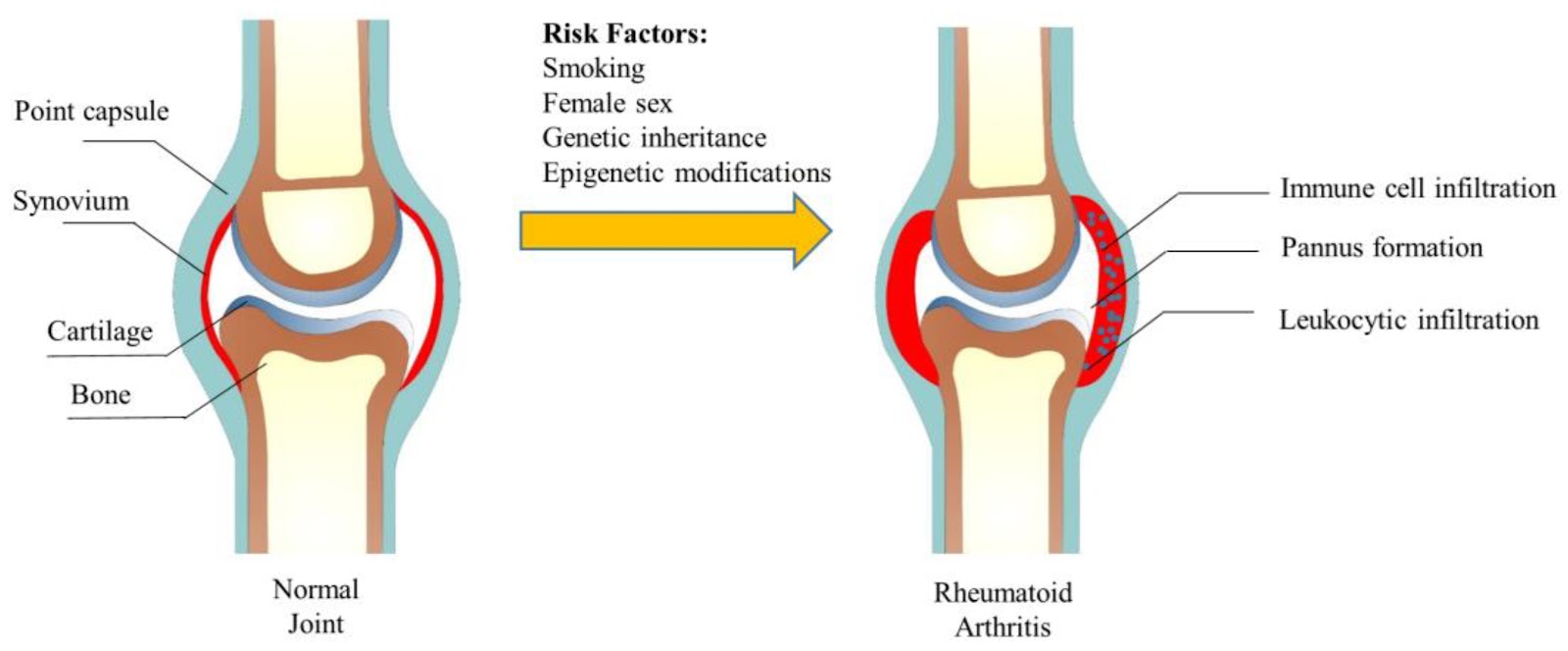

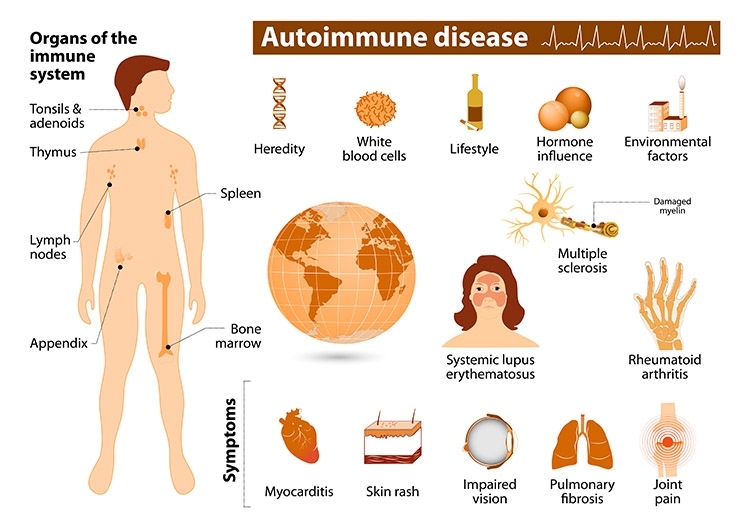

Rheumatoid arthritis, or RA, is an autoimmune and inflammatory disease, which means that your immune system attacks healthy cells in your body by mistake, causing inflammation (painful swelling) in the affected parts of the body.

RA mainly attacks the joints, usually many joints at once. RA commonly affects joints in the hands, wrists, and knees. In a joint with RA, the lining of the joint becomes inflamed, causing damage to joint tissue. This tissue damage can cause long-lasting or chronic pain, unsteadiness (lack of balance), and deformity (misshapenness).

RA can also affect other tissues throughout the body and cause problems in organs such as the lungs, heart, and eyes.

Signs and Symptoms

With RA, there are times when symptoms get worse, known as flares, and times when symptoms get better, known as remission.

Signs and symptoms of RA include:

Pain or aching in more than one joint.

Stiffness in more than one joint.

Tenderness and swelling in more than one joint.

The same symptoms on both sides of the body (such as in both hands or both knees).

Weight loss.

Fever.

Fatigue or tiredness.

Weakness.

Causes

RA is the result of an immune response in which the body’s immune system attacks its own healthy cells. The specific causes of RA are unknown, but some factors can increase the risk of developing the disease.

Risk factors

Researchers have studied a number of genetic and environmental factors to determine if they change person’s risk of developing RA.

Characteristics that increase risk

Age. RA can begin at any age, but the likelihood increases with age. The onset of RA is highest among adults in their sixties.

Sex. New cases of RA are typically two-to-three times higher in women than men.

Genetics/inherited traits. People born with specific genes are more likely to develop RA. These genes, called HLA (human leukocyte antigen) class II genotypes, can also make your arthritis worse. The risk of RA may be highest when people with these genes are exposed to environmental factors like smoking or when a person is obese.

Smoking. Multiple studies show that cigarette smoking increases a person’s risk of developing RA and can make the disease worse.

History of live births. Women who have never given birth may be at greater risk of developing RA.

Early Life Exposures. Some early life exposures may increase risk of developing RA in adulthood. For example, one study found that children whose mothers smoked had double the risk of developing RA as adults. Children of lower income parents are at increased risk of developing RA as adults.

Obesity. Being obese can increase the risk of developing RA. Studies examining the role of obesity also found that the more overweight a person was, the higher his or her risk of developing RA became.

Characteristics that can decrease risk

Unlike the risk factors above which may increase risk of developing RA, at least one characteristic may decrease risk of developing RA.

Breastfeeding. Women who have breastfed their infants have a decreased risk of developing RA.

Diagnosis

RA is diagnosed by reviewing symptoms, conducting a physical examination, and doing X-rays and lab tests. It’s best to diagnose RA early—within 6 months of the onset of symptoms—so that people with the disease can begin treatment to slow or stop disease progression (for example, damage to joints). Diagnosis and effective treatments, particularly treatment to suppress or control inflammation, can help reduce the damaging effects of RA.

Treatment

RA can be effectively treated and managed with medication(s) and self-management strategies. Treatment for RA usually includes the use of medications that slow disease and prevent joint deformity, called disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs); biological response modifiers (biologicals) are medications that are an effective second-line treatment. In addition to medications, people can manage their RA with self-management strategies proven to reduce pain and disability, allowing them to pursue the activities important to them. People with RA can relieve pain and improve joint function by learning to use five simple and effective arthritis management strategies.

Complications

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has many physical and social consequences and can lower quality of life. It can cause pain, disability, and premature death.

Premature heart disease. People with RA are also at a higher risk for developing other chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes. To prevent people with RA from developing heart disease, treatment of RA also focuses on reducing heart disease risk factors. For example, doctors will advise patients with RA to stop smoking and lose weight.

Obesity. People with RA who are obese have an increased risk of developing heart disease risk factors such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Being obese also increases risk of developing chronic conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. Finally, people with RA who are obese experience fewer benefits from their medical treatment compared with those with RA who are not obese.

Employment. RA can make work difficult. Adults with RA are less likely to be employed than those who do not have RA. As the disease gets worse, many people with RA find they cannot do as much as they used to. Work loss among people with RA is highest among people whose jobs are physically demanding. Work loss is lower among those in jobs with few physical demands, or in jobs where they have influence over the job pace and activities.

Manage

RA affects many aspects of daily living including work, leisure and social activities. Fortunately, there are multiple low-cost strategies in the community that are proven to increase quality of life.

Get physically active. Experts recommend that ideally adults be moderately physically active for 150 minutes per week, like walking, swimming, or biking 30 minutes a day for five days a week. You can break these 30 minutes into three separate ten-minute sessions during the day. Regular physical activity can also reduce the risk of developing other chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and depression. Learn more about physical activity for arthritis.

Go to effective physical activity programs. If you are worried about making arthritis worse or unsure how to safely exercise, participation in physical activity programs can help reduce pain and disability related to RA and improve mood and the ability to move. Classes take place at local Ys, parks, and community centers. These classes can help people with RA feel better. Learn more about the proven physical activity programs that CDC recommends.

Join a self-management education class. Participants with arthritis and (including RA) gain confidence in learning how to control their symptoms, how to live well with arthritis, and how arthritis affects their lives. Learn more about the proven self-management education programs that CDC recommends.

Stop Smoking. Cigarette smoking makes the disease worse and can cause other medical problems. Smoking can also make it more difficult to stay physically active, which is an important part of managing RA. Get help to stop smoking by visiting I’m Ready to Quit on CDC’s Tips From Former Smokers website.

Maintain a Healthy Weight. Obesity can cause numerous problems for people with RA and so it’s important to maintain a healthy weight.