Introduction

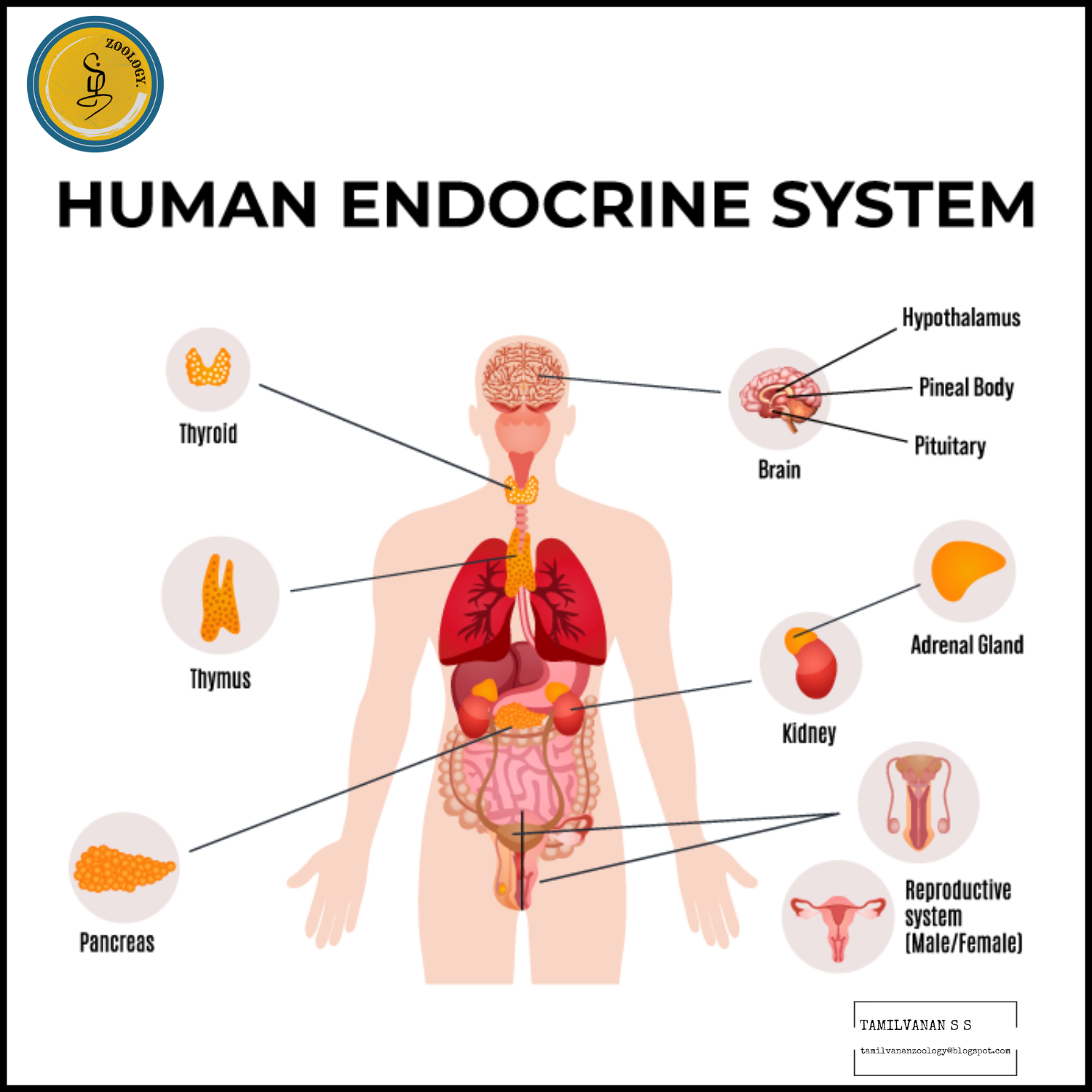

Your pituitary gland (also known as hypophysis) is a small, pea-sized gland located at the base of your brain below your hypothalamus. It sits in its own little chamber under your brain known as the sella turcica. It’s a part of your endocrine system and is in charge of making several essential hormones. Your pituitary gland also tells other endocrine system glands to release hormones.

A gland is an organ that makes one or more substances, such as hormones, digestive juices, sweat or tears. Endocrine glands release hormones directly into your bloodstream.

Hormones are chemicals that coordinate different functions in your body by carrying messages through your blood to various organs, skin, muscles and other tissues. These signals tell your body what to do and when to do it.

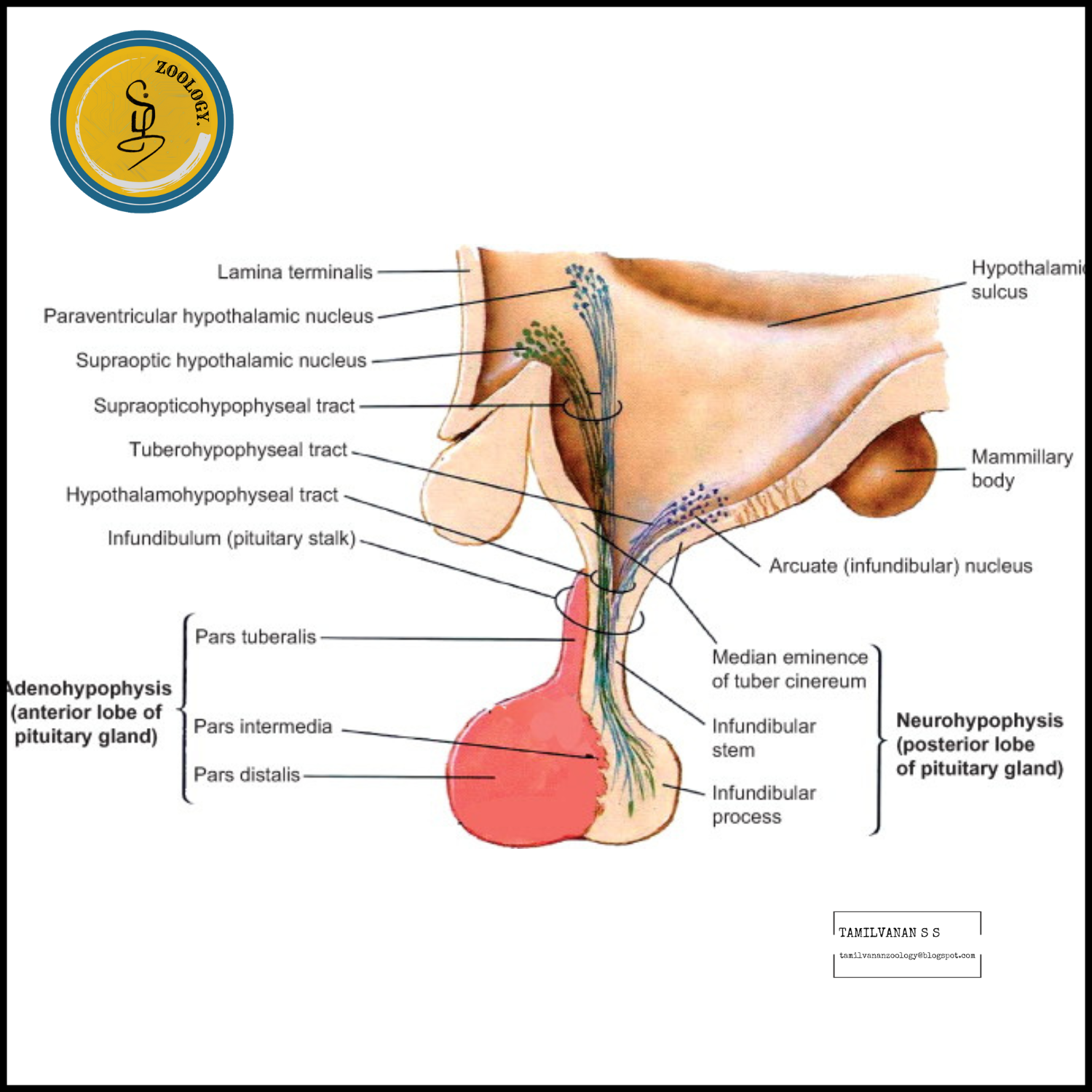

Your pituitary gland is divided into two main sections: the anterior pituitary (front lobe) and the posterior pituitary (back lobe). Your pituitary is connected to your hypothalamus through a stalk of blood vessels and nerves called the pituitary stalk (also known as infundibulum).

Location

Your pituitary gland is located at the base of your brain, behind the bridge of your nose and directly below your hypothalamus. It sits in an indent in the sphenoid bone called the sella turcica.

Parts

Your pituitary gland has two main parts, or lobes: the anterior (front) lobe and the posterior (back) lobe. Each lobe has different functionality and different types of tissue.

The anterior pituitary, the larger of the two lobes, consists of hormone-secreting epithelial cells and is connected to your hypothalamus through blood vessels.

The posterior pituitary consists of unmyelinated (lacking a casing of fatty insulation) secretory neurons and is connected to your hypothalamus through a nerve tract.

Harmones

The anterior lobe of your pituitary gland makes and releases the following hormones:

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH or corticotrophin): ACTH plays a role in how your body responds to stress. It stimulates your adrenal glands to produce cortisol (the “stress hormone”), which has many functions, including regulating metabolism, maintaining blood pressure, regulating blood glucose (blood sugar) levels and reducing inflammation, among others.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH): FSH stimulates sperm production in people assigned male at birth. FSH stimulates the ovaries to produce estrogen and plays a role in egg development in people assigned female at birth. This is known as a gonadotrophic hormone.

Growth hormone (GH): In children, growth hormone stimulates growth. In other words, it helps children grow taller. In adults, growth hormone helps maintain healthy muscles and bones and impacts fat distribution. GH also impacts your metabolism (how your body turns the food you eat into energy).

Luteinizing hormone (LH): LH stimulates ovulation in people assigned female at birth and testosterone production in people assigned male at birth. LH is also known as a gonadotrophic hormone because of the role it plays in controlling the function of the ovaries and testes, known as the gonads.

Prolactin: Prolactin stimulates breast milk production (lactation) after giving birth. It can affect fertility and sexual functions in adults.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): TSH stimulates your thyroid to produce thyroid hormones that manage your metabolism, energy levels and your nervous system.

The posterior lobe of your pituitary gland stores and releases the following hormones, but your hypothalamus makes them:

Antidiuretic hormone (ADH, or vasopressin): This hormone regulates the water balance and sodium levels in your body.

Oxytocin: Your hypothalamus makes oxytocin, and your pituitary gland stores and releases it. In people assigned female at birth, oxytocin helps labor to progress during childbirth by sending signals to their uterus to contract. It also causes breast milk to flow and influences the bonding between parent and baby. In people assigned male at birth, oxytocin plays a role in moving sperm.

Function

The main function of your pituitary gland is to produce and release several hormones that help carry out important bodily functions, including:

Growth.

Metabolism (how your body transforms and manages the energy from the food you eat).

Reproduction.

Response to stress or trauma.

Lactation.

Water and sodium (salt) balance.

Labor and childbirth.

Think of your pituitary gland like a thermostat. The thermostat performs constant temperature checks in your home to keep you comfortable. It sends signals to your heating and cooling systems to turn up or down a certain number of degrees to keep air temperatures constant.

Your pituitary gland monitors your body functions in much the same way. Your pituitary sends signals to your organs and glands — via its hormones — to tell them what functions are needed and when. The right settings for your body depend on several factors, including your age and sex.

Hypothalamus & Pituitary

Together, your pituitary gland and hypothalamus form a hypothalamus-pituitary complex that serves as your brain’s central command center to control vital bodily functions.

Your hypothalamus is the part of your brain that’s in charge of some of your body’s basic operations. It sends messages to your autonomic nervous system, which controls things like blood pressure, heart rate and breathing. Your hypothalamus also tells your pituitary gland to produce and release hormones that affect other areas of your body.

Your pituitary gland is connected to your hypothalamus through a stalk of blood vessels and nerves (the pituitary stalk). Through that stalk, your hypothalamus communicates with the anterior pituitary lobe via hormones and the posterior lobe through nerve impulses. Your hypothalamus also creates oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone and tells your posterior pituitary when to store and release these hormones.

Your hypothalamus makes the following hormones to communicate with and stimulate your pituitary gland:

Corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH).

Dopamine.

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH).

Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH).

Somatostatin.

Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH).

Since your pituitary gland and hypothalamus work together so closely, if one of them becomes damaged, it can affect the hormonal function of the other.

Disorders

Several conditions can affect or are affected by your pituitary gland’s function. The four main categories of issues related to your pituitary gland include:

Pituitary adenomas.

Hypopituitarism.

Hyperpituitarism.

Empty sella syndrome.

Pituitary adenomas

A pituitary adenoma is a benign (noncancerous) growth on your pituitary gland. They make up 10% to 15% of all tumors that develop within your skull.

Pituitary adenomas are usually slow-growing, but if they grow too big, they can put pressure on nearby structures and cause symptoms. They can also compress your optic nerve and lead to vision disturbances (loss of peripheral vision). In rare cases, large pituitary adenomas can bleed internally.

Some pituitary adenomas release excess pituitary hormones. These are called functioning (secreting) adenomas. Others don’t release any hormones. These are called non-functioning adenomas.

There are several different types of functioning pituitary adenomas based on which hormone they release. The most common functioning adenoma is a prolactinoma, which releases excess prolactin. Prolactinomas are typically treated with medication.

Pituitary tumors that grow too big and/or release hormones require treatment, which usually involves surgery.

Hypopituitarism

Hypopituitarism is a condition in which there’s a lack of one, multiple or all of the hormones your pituitary gland makes.

Most cases of hypopituitarism involve one hormone deficiency. A deficiency in two or more of the pituitary hormones is called panhypopituitarism. This typically happens after pituitary surgery or brain radiation.

Hypopituitarism is most often caused by some type of damage to your pituitary gland or hypothalamus.

Specific conditions that involve a deficiency of a pituitary hormone include:

Growth hormone deficiency: This condition happens when your pituitary doesn’t release enough growth hormone (GH). In children, it causes a lack of growth and development and delayed puberty. In adults, it causes metabolic issues.

Central diabetes insipidus: This condition happens when your pituitary doesn’t release enough antidiuretic hormone (ADH, or vasopressin). This causes your body to produce too much urine (pee), and it isn’t able to retain enough water.

Central hypogonadism: This condition happens when your pituitary doesn’t release enough luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). This causes issues with sexual function and development and fertility.

Central adrenal insufficiency: This condition happens when your pituitary doesn’t release enough ACTH. It causes your body to be unable to release cortisol.

Central hypothyroidism: This condition happens when your pituitary doesn’t release enough thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). It causes low thyroid hormone levels.

Treatment of hypopituitarism involves replacing the lacking hormones and monitoring the levels through blood tests.

Hyperpituitarism

Hyperpituitarism happens when your pituitary gland makes too much of one or more hormones. It’s often caused by a functioning/secreting pituitary adenoma (a noncancerous tumor).

Specific conditions that involve an excess of a pituitary hormone include:

Acromegaly: This condition happens when your pituitary gland releases too much growth hormone as an adult. It causes enlargement of certain parts of your body, such as your hands, feet and/or organs, and metabolic issues.

Gigantism: This condition happens when your pituitary gland releases too much growth hormone as a child or adolescent. It causes rapid growth and very tall height.

Cushing’s disease: This condition happens when your pituitary gland releases too much ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone), which causes your adrenal gland to make too much cortisol. It causes rapid weight gain in certain areas of your body and high blood sugar, which can develop into Type 2 diabetes.

Hyperprolactinemia: This condition happens when your pituitary gland releases too much prolactin. It causes infertility and milky nipple discharge (galactorrhea).

Empty sella syndrome

Empty sella syndrome (ESS) is a rare condition in which your pituitary gland becomes flattened or shrinks due to issues with the sella turcica, a bony structure at the base of your brain that surrounds and protects your pituitary gland. The sella turcica is a saddle-like compartment. In Latin, it means “Turkish seat.”

Empty sella is a radiographic diagnosis. Oftentimes, it doesn’t translate into a true medical condition and is often found by accident on imaging.

In some cases, ESS may cause certain symptoms, including hormone imbalances, frequent headaches and vision changes. However, if the pituitary hormone levels are within normal ranges, it’s not a cause for concern.

Symptoms

Large pituitary adenomas (macroadenomas), which are benign (non-cancerous) tumors that develop on your pituitary gland, can put pressure on or damage nearby tissues. This can cause the following symptoms:

Vision problems (loss of peripheral vision).

Headaches.

Hormonal imbalances from pituitary hormone excess or deficiency.

Pituitary hormone imbalances can cause many different symptoms depending on which hormone is affected, including:

A lack of growth or excess growth in children.

Male and female infertility.

Irregular periods.

Unexplained weight gain or weight loss.

Depression and/or anxiety.

It’s important to talk to your healthcare provider any time you’re experiencing new, persistent symptoms. They can order some simple blood tests to see if your symptoms are related to hormone issues or something else.