Introduction

Gastrulation is a critical process during week 3 of human development. Gastrulation is an early developmental process in which an embryo transforms from a one-dimensional layer of epithelial cells, a blastula, and reorganizes into a multilayered and multidimensional structure called the gastrula. In triploblastic organisms such as reptiles, avians, and mammals, gastrulation attains a three tissue-layered organism composed of endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. Each germ layer corresponds to the development of specific primitive systems during organogenesis.

In addition to setting the embryo up for organ formation, gastrulation provides a mechanism to develop a multileveled body plan that demarcates anatomical axis formation. These axes are the dorsal/ventral axis, also termed the anterior/posterior or rostral/posterior axis, and the cranial/caudal or superior/inferior axis. Gastrulation also promotes the retention of global left and right symmetry and the loss of bilateral symmetry in specific organs such as the heart.

Development

After fertilization, the single-celled zygote undergoes multiple mitotic cleavages of the blastomeres to change from a two-celled to a 16-celled ball or morula. The morula begins as a solid mass of totipotent blastomeres that undergoes compaction and cavitation to transform into the blastula (non-mammalian term) or blastocyst (human development). Within the blastocyst, two tissue layers differentiate: an outer shell, known as the trophoblast, and an inner collection of cells termed the inner cell mass (ICM). Cells within the outer shell bind together via gap junctions and desmosomes to undergo compaction, ultimately forming a water-tight shell called the trophoblast.

The outer trophoblast will develop into structures that provide nutrients, help the growing embryo implant in the uterine lining, and contribute to the formation of the placenta. Additionally, the trophoblast cells are essential in the cavitation of the solid morula into a hollowed ball of cells with an internal cavity. Trophoblast cells utilize the active transport of sodium ions and osmosis of water to form a fluid-filled cavity known as a blastocoel.

The cells remaining after blastocoel formation are pluripotent ICM progenitor cells, which give rise to the distinctive formation of the fetus. Rather than being arranged as a solid sphere of cells, the ICM is pushed off to one side of the sphere formed by the trophoblast. Together the trophoblastic layer, blastocoel, and inner cell mass are the characteristic features of the human blastocyst.

From zygote to blastocyst formation, the organism is surrounded by the zona pellucida, a layer of the extracellular matrix that plays a role in the protection and prevention of implantation into the uterine tubes. During blastocyst formation, the zona pellucida begins to disappear, allowing the ball of cells to proliferate, differentiate, change shape, and eventually implant into the uterine wall.

During implantation, the trophoblastic layer surrounding the blastocyst further differentiates into two functionally distinct layers. The outer trophoblast, known as the syncytiotrophoblast, releases proteolytic enzymes to assist with endometrial implantation. This layer also releases human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, necessary in regulating progesterone secretion), the protein used in many pregnancy tests. The inner trophoblast layer, known as the cytotrophoblast, is a single sheet of cells surrounding the extraembryonic mesoderm. Within the cytotrophoblast is the ICM. During the second week of human development, the cells of the ICM spread into a flattened tissue layer and differentiate into a two-layered tissue containing epiblast (columnar epithelial cells) and hypoblast (cuboidal epithelial cells), which are together known as the bilaminar embryonic disc.

The formation of the bilaminar embryonic disc sets the dorsal/ventral axis as the epiblast cell layer is positioned dorsal to the hypoblast. The anatomical location of the bilaminar disc is found between the amniotic cavity and the primitive yolk sac. The cells of the epiblast stretch to form a semi-sphere known as the amniotic cavity, while the cells of the hypoblast extend to surround the yolk sac. On the hypoblast is a raised area of columnar cells known as the prechordal plate; this is the earliest delineation of cranial from caudal. Development of the bilaminar embryonic disc directly precedes gastrulation, the stage in week 3 of development that involves the transformation of the human blastocyst into a multilayered gastrula with endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm.

Cellular:

The beginning of gastrulation is marked by the appearance of the primitive streak, a groove in the caudal end of the epiblast layer. Thus, the formation of the primitive streak firmly establishes the cranial/caudal axis. The primitive streak initially forms via a thickening of cells near the connecting stalk. As cells proliferate and migrate toward the midline of the embryo, the thickening elongates to become linear in shape, thus the term primitive steak.

The cranial end of the embryo seems to play an important role in initiating gastrulation. At the cranial end of the primitive streak, epiblast cells ingress at a greater rate forming a circular cavity known as the primitive pit. As the primitive streak elongates, migrating epiblast cells join the streak at the cranial end, forming a mass of cells around the primitive pit. This mass is called the primitive node, which becomes the primary tissue organizer where transcription factors and chemical signaling drive the induction of tissue formation. Known signaling factors and pathways in primitive streak formation include transforming growth factor-beta (TGFB), Wnt, Nodal, and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), which are discussed in more detail in the molecular section.

Epithelial cells in the lateral edge of the epiblast layer undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal cellular transition to delaminate (detach) and migrate down or into the primitive streak. The movement of epiblastic mesenchymal cells down the primitive streak is known as ingression. The first set of cells to move down the primitive streak integrate into the hypoblast layer and form endoderm, the first of the three germ layers. The second set of cells to detach and ingress will fill the space between the endoderm and epiblast layer to form the second germ layer, mesoderm. Multiple mesodermal structures will develop: cells that move into the body stalk will help to form extraembryonic mesoderm, and later the umbilical cord, cells passing through the primitive pit become the notochord or paraxial mesoderm, and other cells coming through the primitive streak become lateral plate or extraembryonic mesoderm. Finally, the remaining epiblast cells will transform into the final germ layer, ectoderm.

Cell proliferation and ingression continue in all directions as the embryo grows; however, the primitive streak will always expand directionally from the caudal to the cranial end and then regress in the opposite fashion. Regression occurs after the formation of the intra-embryonic mesoderm, and the primitive streak should completely disappear by the end of the fourth week — a lack of primitive streak regression results in clinical abnormalities.

After the three germ layers have formed, the newly produced structure (the trilaminar embryonic disc or gastrula) is primed for organ system formation, which relies highly on direct interaction and induction events between the endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. Cells continue to invaginate through what is now called the primitive node. The cells begin to form a hollow tube extending from the cranial end to the prechordal plate, known as the notochordal process. As the embryo grows in each direction, the notochordal process grows longer until it fuses with the endoderm to form the notochordal plate. Once the fusion is complete, there is a free passageway between the amniotic cavity and the yolk sac, known as the neurenteric canal, or canal of Kovalevsky.

Cellular movement (Morphogenetic movement):

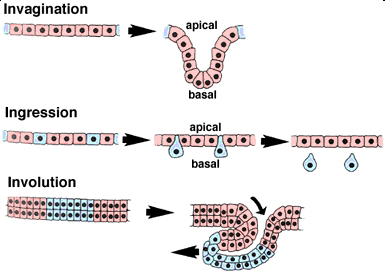

Gastrulation is complicated, Because of this, it is helpful to break the movements of gastrulation down into their component events wherever possible. In general, sheets of cells can engage in only a limited number of morphogenetic movements. This "morphogenetic repertoire" is helpful to keep in mind when we are presented with what seems to be an incomprehensible change in the shape of the embryo. Through careful observation and experimental manipulation, gastrulation can be analyzed in convenient organisms such as sea urchins. On this page, the various major morphogenetic movements that occur during gastrulation in diverse organisms are schematically represented. Some of these movements are only performed by epithelial cells, while others can be performed by both bona fide epithelial cells and by deeper, non-epithelial cells that nevertheless behave as integrated sheets of cells. The latter are poorly understood, but are common in amphibians as well as in higher vertebrates.

Invagination

During invagination, an epithelial sheet bends inward to form an inpocketing. One way to think of this in three dimensions is to imagine that you are poking a partially deflated beach ball inward with your finger. The resulting bulge or tube is an invagination. If the apical side of the epithelium forms the lumen (central empty space) of the tube, then the movement is termed invagination. If the lumen is formed by basal surfaces, then the movement is termed an evagination.

Ingression

During ingression, cells leave an epithellial sheet by transforming from well-behaved epithellial cells into freely migrating mesenchyme cells. To do so, they must presumably alter their cellular architecture, alter their program of motility, and alter their adhesive relationship(s) to the surrounding cells. Primary mesenchyme cells are an example of a mesenchymal cell type that emigrates out of an epithelium (do you know which one?).

Involution

During involution, a tissue sheet rolls inward to form an underlying layer via bulk movement of tissue. One helpful image here is of a tank tread or conveyor belt. As material moves in from the edges of the sheet, material originally at the sites of inward rolling (shown in blue here) is free to move further up underneath the exterior tissue.

Epiboly

During epiboly, a sheet of cells spreads by thinning. i.e., the sheet thins, while its overall surface area increases in the other two directions. Epiboly can involve a monolayer (i.e. a sheet of cells one cell layer thick), in which case the individual cells must undergo a change in shape. In other cases, however, a sheet that has several cell layer can thin by changes in position of its cells. In this case, epiboly occurs via intercalation, one of the other movements described on this page.

Intercalation

During intercalation, two or more rows of cells move between one another, creating an array of cells that is longer (in one or more dimensions) but thinner. The overall change in shape of the tissue results from cell rearrangement. Intercalation can be a powerful means of expanding a tissue sheet. A specialized form of intercalation is convergent extension, which is described on this page.

Convergent Extension

During convergent extension, two or more rows of cells intercalate, but the intercalation is highly directional. Cells converge by intercalating perpendicular to the axis of extension, resulting in the overall extension of the tissue in a preferred direction. If we had a way to label cells from rows on either side of the axis of extension, they would be found to mix with one another as a result of these oriented intercalation events.

Molecular level:

Primitive Streak

The initiation of the primitive streak is based upon a system of signaling pathways working to both positively and negatively regulate downstream expression. The combination of TGFB, Wnt, Nodal, and BMPs is important in primitive streak development. The interplay between Wnt and TGFB signaling seems to be the inducer of the formation of the primitive streak. Specifically, Vg1 (a member of the TGFB family) has been shown to induce streak formation and to prevent formation with Vg1 misexpression at the posterior marginal zone. Vg1 acts on Nodal to continue the chemical cascade to streak formation. To ensure the proper location of the streak on the epiblast, the hypoblast releases antagonists of Nodal signaling.

Additionally, the induction of streak formation can be regulated by Wnt factors; not only has upregulated Wnt induced streak formation, but the use of Wnt antagonists such as Dkk-1 and Crescent prevents the formation of the streak. Finally, BMP signaling has been shown to regulate streak formation. Closer to the streak, BMP concentration is low, with the surrounding embryo exhibiting higher levels of active BMP. In addition to this, BMP inhibitors cause the formation of a streak in chick embryos. As seen in BMP and other signaling, concentration gradients are typical through most of gastrulation. Different concentrations of signaling factors allow cells to differentiate into unique tissues.

Endoderm

Endoderm is the embryonic precursor to the thyroid, lungs, pancreas, liver, and intestines, which evolve from four consecutive steps developmental steps: proliferation and induction of pluripotent stem cells, the separation of stem cell-derived endoderm versus mesoderm germ layers, anterior-posterior patterning, and bifurcation of the liver and pancreas. Cells near the anterior portion of the primitive streak will express Forkhead box A2 (Foxa2) to become definitive endoderm (DE). The DE will pattern itself into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut via mesodermal induction during embryonic folding with foregut cells expressing Hhex, Sox2, and Foxa2 and the hindgut expressing different homeobox genes Cdx1, Cdx2, and Cdx4. The upregulation of TGFB signaling promotes pancreas formation with BMP and FGF/MAPK signaling to specify the liver. The specification of the respiratory bud starts with the expression of the Nbx1-2gene. Complex signaling between the respiratory bud epithelium and mesoderm involves FGF and FGFR interactions to promote the growth of the respiratory bud.

Mesoderm

Epiblast cells invaginating through the primitive streak that express high levels of a fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) are fated down a path towards becoming mesodermal cells. More specifically, they will end up as paraxial, intermediate, or lateral plate mesoderm, which will correlate to different tissues as the embryo develops.

Notochord

Progenitor cells from the primitive node and primitive pit migrate to initiate notochord formation. Epiblast cells from the floor plate of the amniotic cavity fill in the notochord to form a thick rod-like structure down the midline of the embryo. Providing support and serving as an induction center for surrounding cells, the notochord in vertebrates extends throughout the entire length of what will be the vertebral column and reaches as far as the midbrain. The notochord develops first, then mesodermal cells grow medially to surround it. The notochord is only present in developing organisms with the primary goal of patterning the surrounding tissues. The notochord secretes Sonic Hedgehog, Chordin, and Noggin in a morphogenic gradient pattern where the highest concentration is near the notochord with diffusion outward. These bind to receptors on target cells to induce specification and differentiation events in the neural plate, somites, and ectoderm.

Mesoderm divides into three main categories: paraxial (or axial), intermediate, and lateral (or lateral plate) mesoderm, which are the embryonic precursors to a large variety of cells and tissues, including smooth, cardiac, and skeletal muscle, kidney, reproductive organs, the muscles of the tongue and the pharyngeal arches, connective tissue, bone, cartilage, the dermis and subcutaneous layers of the skin, dura mater, vascular endothelium, blood cells, microglia, and adrenal cortex.

Cells of the paraxial mesoderm cells first organize to form somitomeres. As the somitomeres develop into somites in a cranial-to-caudal fashion, the outer cells undergo a mesenchymal to epithelial transition, which serves as a distinct boundary between individual somites. Individual somites then separate into cranial and caudal portions, followed by the cranial portion of each fusing with the caudal portion of the somite directly anterior to it. Distinct regions of each somite (sclerotome, dermatome, myotome) become specific tissue and cell types as the body matures. The skull, vertebral column, and brain meninges develop from the mesoderm surrounding the neural tube and notochord.

The intermediate mesoderm connects the paraxial mesoderm with the lateral plate and differentiates into urogenital structures.

The lateral plate mesoderm splits into a parietal (or somatic) layer to aid lateral body fold wall formation and a visceral (or splanchnic) layer involved in gut tube formation.

Ectoderm

The interplay between BMPs and Hox genes is integral to differentiating the remaining epiblast tissue into the ectoderm. This is especially important for the surface ectoderm and what will become the neuroectoderm, setting up the brain and spinal cord.

The notochord is the main inductive tissue delineating neuroectoderm from the remaining ectoderm that will become skin. The entire presumptive ectoderm plate expresses BMP and TGFB. Noggin and Chordin secretion from the notochord diffuses into the ectoderm directly anterior to the notochord and binds to receptors in the overlying ectoderm to block BMP. The blockade of BMP specifies the tissue to neural ectoderm, while the remaining ectoderm, which still expresses BMP, will become skin.

It is theorized that the neurenteric canal forms to maintain pressure equilibrium between both chambers. Later in development, the two edges of the notochordal plate will fuse into a solid mesodermal rod known as the notochord. The notochord is a critical embryologic structure that provides structural support and marks the midline of the embryo. Chemical and physical interactions between the notochord and dorsally situated ectoderm produce neuroectoderm and, eventually, the nervous system.

Function:

Gastrulation occurs during week 3 of human development. The process of gastrulation generates the three primary germ layers ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm. Gastrulation primes the system for organogenesis and is one of the most critical steps of development.

The endoderm is the innermost layer, which gives rise to the gastrointestinal tract, the lining of the gut, the liver, the pancreas, and portions of the lungs and glandular tissues. The mesoderm gives rise to the musculoskeletal system, including its connective tissue, the non-epidermal portions of the integumentary system, the circulatory system, the kidney, and the internal sex organs. The ectoderm is the outer layer of the embryo, which gives rise to the external ectoderm (epidermis, hair, nails) and the neuroectoderm (neural crest and neural tube), along with the lens of the eyes and the inner ear.

Another important function of gastrulation is to establish directionality within the developing embryo. Cranial/caudal directionality is established by the placement of the prechordal plate and the path of the primitive groove. The layering of the epiblast and hypoblast establishes the dorsal/ventral axis.